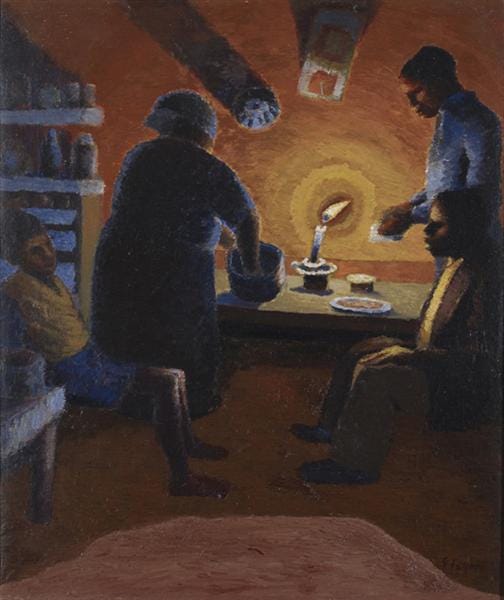

Gerard Sekoto | Boy and the Candle 1943

I am the very specimen

Of a sleepwalking gentleman

If I die before I wake

Save my dreams for another day.

—Shakey Graves, Counting Sheep

Find an audio reading of this Black Eyed Story above.

When I was nine years old, my second oldest sister, Michele, turned up pregnant at the ripe age of 16 and, according to the adults in the room, her whole world was done for, her whole life ruined.

If they’d been to Sunday School with me just the week before our family’s glad tidings of great joy, Mrs. Flowers would’ve taught them that Mary, an unwed teenaged girl, could have been any one of us who’d gotten herself into “a pickle of a situation.” Maybe then, they would’ve known that my sister’s world was just beginning – and like me, they would’ve been waiting for her to receive her visitation from Gabriel the Archangel.

One of my favorite songs is a quiet but heavy lullaby by Shakey Graves called Counting Sheep (*find a video below). His ghostly voice floats on an ethereal wind like the one that greeted the prophet Elijah in the cave – only instead of asking “What are you doing, here,” it whispers a repeated warning that feels like an unsettling condemnation:

Don’t you take a bow at the last curtain call/Thinking you’re nobody’s nothing after all.

But Graves ends the song with a sigh of validation:

You’re somebody’s something after all.

This is the song of my sister Michele’s firstborn, Sean Michael Alvis. He came to us when I was ten and his mother just seventeen, and my family was made all brand new – new as the world was made new when Mary laid Jesus in the manger.

This is not sacrilege. We’re meant to love this way. We’re meant to believe that every baby is the arrival of the second coming, a reminder for us to begin again. Anything less is to do exactly what Shakey Graves warns against: taking a bow at the last curtain call, thinking that we’re nobody’s nothing after all. If nothing else, the Nativity is there to remind us that we are all somebody’s something. Every human being is a heralded, swaddled manger baby, and the stars do sing.

Twelve years ago in the creeping midnight hours on the eve of Thanksgiving, believing that he was nobody’s nothing, Sean took a bow and ended his life. He was 33 years old.

Grief, wonder, awe – a pondering of a resurrected life…

the arrival of light after a long stretch of years of darkness.

What no one ever talks about is Mary after Jesus’s death. We see her at the cross and then nothing else. In gospel after gospel we’re told that Mary pondered this child of hers. Surely, she continued to ponder his spectacular resurrection from the tomb - and yet, nothing is written.

I suppose back in antiquity, no one cared much about the pondering of grieving mothers. I suppose no one wanted to sit with the grief or wonder or awe. Jesus’s birth, death and resurrection were a knot of all three.

As was Sean’s.

What child was this, who laid in rest on my teenage sister’s lap sleeping? My family couldn’t say. But oh my, we cooed and sang over him, so beautiful, so beautiful he was. For 33 years he bewildered all of us and I’m quite sure my sister pondered. I’m quite sure she still ponders.

This year for Thanksgiving, I went home to be with my family for the first time in nineteen years. My sister Michele drove through the night from Mississippi to Ohio to my sisters Mia and Debbie’s apartment so she could be there with us. When my family—myself, Simon and Max— finally arrived, my sister Michele was the first to greet us even though it wasn’t technically her door, falling into us, sobbing, telling us how much she loved us, how much she had missed us. It was the anniversary of Sean’s death. Grief, wonder, awe – a pondering of a resurrected life between us, the arrival of light after a long stretch of years of darkness.

Advent means the arrival of something long awaited. For the first time in nineteen years, my entire family came home, ghosts and all.

Gerard Sekoto | Family with Candle 1942

Traditionally, once a week for the four weeks of advent, a candle is lit. Each flame represents a different illumination of a symbolic shared humanity. A light for hope. A light for peace. A light for joy. A light for love. This circle of light is placed within a wreath of evergreens symbolizing life that is ever-green, ever-alive, long after our boughs are clipped and hung out to dry.

In our family, my siblings and I are the flickering flames and Sean is our ever-green, ever-alive wreath that holds the light that was there in the blackness of that night twelve years ago and is still here in this bleak, dark grief remembered.

I love to think that Gabriel came to Mary under cover of night like the heavenly host visited the shepherds. I like to think of this Divine Otherworldly Light touching earth because She knows darkness quiets us and light tenders us. And I can honestly say that for the past twelve years, my spades-card-table-slapping, thigh-slap-laugh-cackling, finger-pointing-fighting-cussing family has never been more quiet and tender. We know that even though we are shrouded in death tombs of deep darkness, light is coming, and our thin flames will keep us warm while we await its arrival.

Our collected lives, dark and light, are the manger that cradles a new beginning.

What you must know is that from the outside looking in you would’ve perceived that my family is poor and hardworking, open and forgiving, and quick to make itself a family to strangers.

You would’ve seen my other two sisters, brother, my cousins, the building maintenance man, my other sister Mia’s ex-husband, her best friend, my other two nephews, my great nephew, my three older cousins, my half-brother (fully equipped with a government-issued ankle bracelet), his girl for that evening, and a whole host of others breezing in and out of a two bed/one bath apartment as if it were the lobby of The Ritz.

You would’ve seen a kitchen with every surface covered with food for the Gods – chitlins, greens and ham hocks, green beans with fatback, dressing, sweet potatoes, turkey, gravy, potato salad, crescent rolls, potato rolls, and a pan of macaroni and cheese to which we all bowed.

You would’ve heard every manner of conversation, from the Miami Dolphins to get-rich-quick-schemes to a running list of who died “just this morning,” or “just last week,” or “sometime last month.” You would’ve heard everyone’s work schedule – who was working a double shift and who needed to wrap their plate so that they could make it to their shift on time.

You would’ve heard a joy that only true poverty can make and your heart would’ve swelled with the blessing. You would never have guessed that the amount of loss in those rooms was greater than our national debt. You couldn’t have calculated the combined weight of worries and heartbreaks no more than you could’ve weighed the ones in the manger.

Surely, there were worries and heartbreaks there between Mary and Joseph, who must’ve been weary with travel and longing for home. And there must’ve been some concerns passed between the sleep-deprived shepherds, too, who weren’t accustomed to such a direct welcome. Angel visitations aren’t common occasions, not even in the Bible. I still wonder if my sister Michele ever had hers. I’m still waiting for one of my own (psst… Most Divine, your servant is right here and I am listening).

If you were on the outside looking in on my family’s Thanksgiving, you would’ve heard a lot of things (at one point, my husband began recording conversations), and your eyes would’ve feasted on more than your pupils could hold – and never once would you have felt unsafe or unwelcome. That’s what light does in the darkness – it welcomes “your tired, your poor/your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” so to speak. It lifts “a lamp beside the golden door,” even in the tiny apartments of poor, grieving families.

This season, in the poverty of our divided American family, may we realize that we are the arrival that we’ve been waiting for. Yes, of course, you can still look to the story of the Messiah in the manger, but if only to see the truth of this: we are the Divine Second Coming, the angels, the angelic choir of the Heavenly Host. Our collected lives, dark and light, are the manger that cradles a new beginning.

This season, whatever you do in this darkness, don’t take a bow at the last curtain call, thinking you’re nobody’s nothing. Lean closer to the light and see that you are somebody’s something, somebody’s candle in the night.

MEDITATION

A Candle In The Night

by Nathan Spoon

Stone is tender

to lichen.

Lichen is tender

to the earth and its other

inhabitants. What are

you and I tender to?

When a black hole

swallows a star,

it must do so tenderly, since

a universe hinges

on tenderness.

At midnight

your candle burns

with tenderness,

dream-like in an amber

votive, its flame

flickering tenderly.

Oh. Marcie. This. Just.

Amen and amen and amen.

So. Beautiful. Advent is tricky for me, I love the symbolism and the tradition, I’m still just untangling the toxic parts from the beautiful parts and trying to determine what still resonates and what really doesn’t. But this feels so real and true and messy and beautiful, thank you so much for sharing!