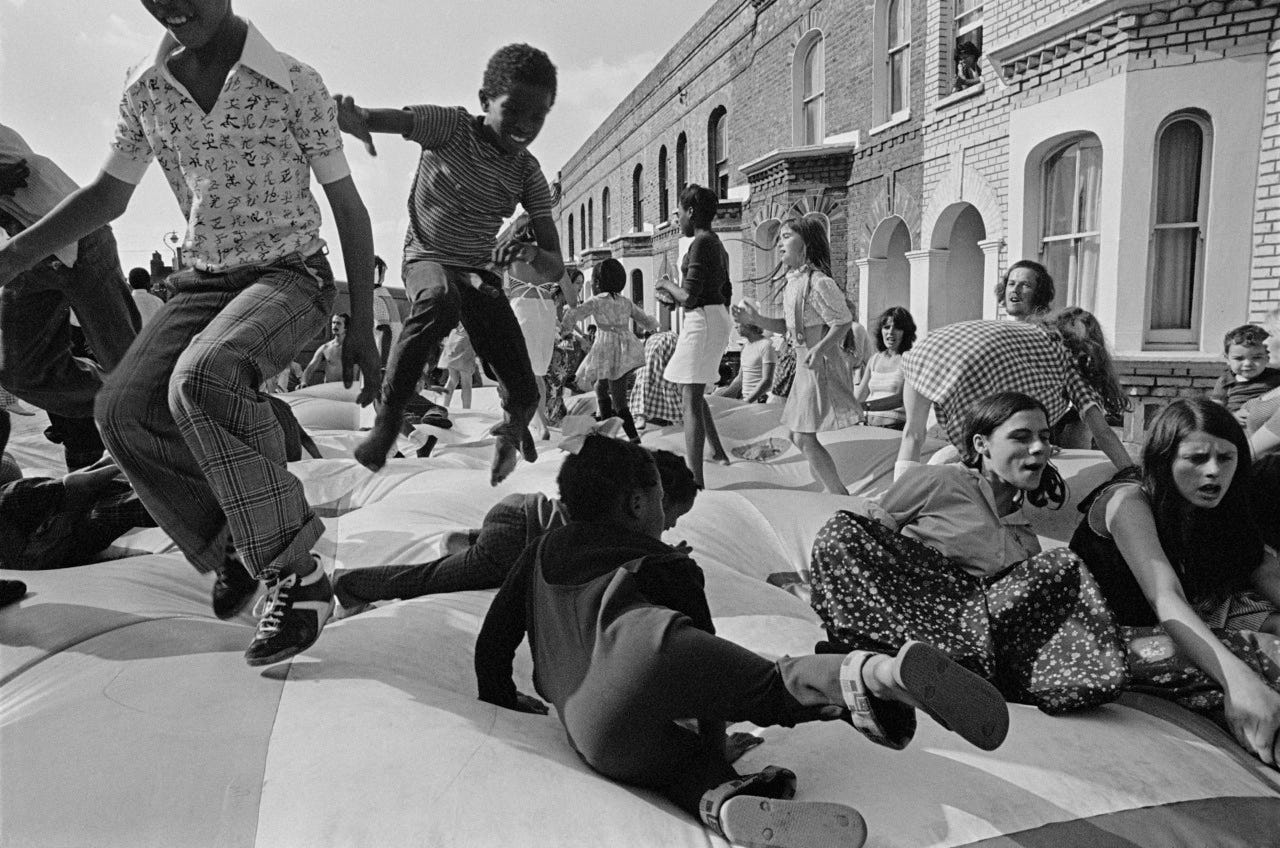

Chris Steele-Perkins. London, England 1974

An earlier rough draft of Langston Hughes' famous poem Harlem goes like this:

I was born here, he said,

watched Harlem grow

until colored folks spread

from river to river

across the middle of Manhattan

out of Penn Station

dark tenth of a nation,

planes from Puerto Rico,

and holds of boats, chico,

up from Cuba Haiti JamaicaI’ve seen them come,

Wondering, wide-eyed, dreaming and dark.

What happens to a dream deferred?Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—and then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust, and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?Pouring out of Penn Station

a new nation—

but the trains are late.

The first time I heard the revised and finished copy of this poem was from a White, fourth-grade, teacher’s lips. And even though her incantation was infused with an Ohioan, Midwestern-slow yawn that simply could not be helped, it was as if my sole Black soul unfurled the tightness in her inflection and added the “jazz, ragtime, swing, boogie-woogie, and be-bop” where Mr. Hughes intended. And I was the only one who understood his meaning, the only one who could hear what Hughes described as “conflicting changes, sudden nuances, sharp and impudent interjections, broken rhythms, and passages sometimes in the manner of the jam session, sometimes the popular song, punctuated by the riffs, runs, and disc-tortions of the music of a community in transition.” I, and I alone, sat, a tale-of-a-fourth-grade-nothing-negress who finally felt called on to answer a question that only I understood:

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—and then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust, and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

Chris Steele-Perkins. London, England 1974

“A community in transition” was the story of every Black person I ever knew. Everyone was always moving towards something: a high school diploma, a job at the Ford plant, a new man with a pension, a new used car, or a trip back home down South. We were perpetually migrating even when we were standing still. Always escaping to something better. Always moving to save our Black skin.

One summer, when my oldest sister was in her early 20s, she moved out to California. A friend had “made it” out there to the land of sunshine and movie stars. I heard my mother telling someone over the phone that my sister “packed up her shit… You know these kids think they know somethin’ once they get grown when they don’t know a got-damn thing. But I tell you what – she ‘bout to find out. This shit ain’t easy.”

By “shit,” my mother meant the bills and putting food on the table, the bills and keeping a job, the bills and making sure there’s enough gas in the car, the bills and back-to-school shopping, the bills and the bills and the bills.

My sister didn’t last a year out west.

I’ve seen them come,

Wondering, wide-eyed, dreaming and dark.

What happens to a dream deferred?

Chris Steele-Perkins. London, England 1974

When my sister returned to her old bedroom with her same old bed and same old dresser and same old closet left untouched and just as she left them, it was a marvel that she didn’t slap and smash and kick away all those smirking surfaces. “Oh, you thought this shit was easy,” every vapid corner in her room seemed to say. “Well, welcome home.”

And we, the soured left-behind, treated her no better. Like jilted lovers we couldn’t help but to rejoice a little seeing her head humbled and hanging low. I distinctly remember averting my eyes as she walked through the door like a defeated veteran with no more than a duffle bag’s worth of souvenirs to remind her later in life that, once upon a time, she’d been brave.

We, the ones who stayed, were self-righteous in our commitment to not even think of attempting to escape. “And go where,” we’d say - our audience knowing that this wasn’t really a question. That right there is what happens to a dream deferred, Mr. Hughes: it settles and shoots arrows at those who dare to take one step forward – one hopelessly cynical, doomed-to-fail false move forward. We migrate without moving, without dreaming. We migrate in ever-tightening concentric woebegone circles, blue as a sax solo.

I never did ask my sister what happened out west. Where’d her fire go? What happened to her sunrise? What did she see out there that sent her running back to these thirsty roots? What dark star extinguished her wondrous, wide-eyed dreaming? What darkness crept in and snuffed the living daylights out of her?

Chris Steele-Perkins. London, England 1974

Langston Hughes’ Harlem was the only poem written by a Black writer we studied in the fourth grade. Just that one siren, juke-joint-of-a-song. We studied it again in fifth and sixth grades and again in seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth. And then it just disappeared from the curriculum.

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—and then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust, and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.Or does it explode?

Chris Steele-Perkins. London, England 1975

Two weeks ago I learned that Mr Hughes wrote a whole book of poetry for children called The Dream Keeper And Other Poems. The dedication reads:

To My Brother — L.H.

To the Children Who Dream — B.P.

The book was published in 1932 with 59 poems for Black children. Could you imagine if my mother, my aunties, my cousins, me and my brother and sisters were given a book of poems that someone wrote just for us? Could you imagine if a teacher assigned a book like that to the whole classroom? Perhaps my sister would still be in California picking lemons from her very own lemon tree in her very own backyard. Perhaps I would have published my first book thirty years ago. Perhaps we might’ve been a little more content, if not happy, had we known that someone thought of us so long ago.

One of the poems in the collection is simply called Dreams, and reads as follows:

Hold fast to dreams

For if dreams die

Life is a broken-winged bird

That cannot fly.Hold fast to dreams

For when dreams go

Life is a barren field

Frozen with snow.

Oh! the things I might have dreamed if only I’d been warned that even worse than a dream deferred is a dream never dreamt at all.

I am once again rended wordless by the beauty & insight of your prose. I understand more now.

It is somber and true and real, all at once, what you have described.