"The night Max wore his wolf suit and made mischief of one kind and another his mother called him 'WILD THING!' and Max said 'I'LL EAT YOU UP!' so he was sent to bed without eating anything.”

Maurice Sendak, Where the Wild Things Are

"I only have one subject. The question I am obsessed with is: How do children survive?"

Maurice Sendak, Maurice Sendak: A Celebration of the Artist and His Work

When our kid finally told us the whole truth about themselves, when they finally told us absolutely everything—come what may, win or lose, no matter what happens next—the moment was a little lackluster. Not in a somber way, but just uneventful.

But maybe uneventful isn’t the right word because, of course, that moment was everything. It was what we’d been waiting for, praying for in earnest. And perhaps because we, their parents, were so earnestly waiting, we were much too relieved to be bothered with all the mechanics of their arriving to the moment when they finally told us all the things: Gay. Trans. Non-binary. They.

Days later, I asked, “Would you like a new name?” Their old name didn’t suit who they said they were and I wanted to get it right this time. A week or two later, they told me, “Yes.” They admitted they no longer used their dead name in their classes. Professors and students were calling them a nickname friends had picked—a name that I, their own mother, didn’t know and hadn’t been told.

An awful dawning rose in ombré ribbons of graduating hues ranging from complete ignorance, fading into revelation, bleeding into a thin wisp of bewilderment: Our kid had already come out. We weren’t their first stop. Not their first choice. They were already living a life, an identity, apart from us.

Both Simon and I were raised to be good Christians. Good Christians were members of a good bible-teaching, bible-preaching church. And good Christians went to their good bible-teaching, bible-preaching church every Sunday. And good Christians served at their good church as part of the welcome wagon opening doors and handing out programs and smiling at strangers. Or they served as parking lot attendants, controlling traffic flow, waving and smiling at cars packed with friends and strangers. Or they served caring for children, smiling and reassuring young parents, training and teaching the next generation “the way in which they should go.” Or if they were exemplary and good, they served on the frontlines as prayer warriors or as part of the worship team. Exemplary and good Christians served and tithed so much so that the lead pastor knew them by name. Simon and I were exemplary and good Christians.

We were so exceptionally good that we took our serving and giving and praying and teaching beyond our church parking lot, outside the walls of our home and into the world. No, we weren’t missionaries, we were foster parents. Correction: we were a foster family. I wanted everyone to know that our kid was also “serving”. This was our offering as a family. We were so, so obnoxiously good.

Our good bible-teaching, bible-preaching church had a motto that our family adopted: Come as you are (but don’t stay as you are). Before every Sunday service began, a pastor or employee of the church would stand center stage to welcome newcomers, proudly proclaiming, “Come as you are.” But the parenthesized part of our motto was never as loudly pronounced, “but don’t stay as you are.” We were a church for seekers. We didn’t want to spook those who’d already regretted their decision to be there. We didn’t want to overwhelm the non-committals. So, “Come as you are,” was always spoken with our arms thrown wide open. “But don’t stay as you are,” was always said with a sly, teasing chuckle.

Are you an addict? Come as your are. Are you a skeptic? Come as you are? Are you divorced? Come as you are. Are you living in sin with your partner? Come as you are. Are you a backslider, a swinger, a good-for-nothing womanizer, a player, a felon, a home-wrecker, a thief, a pill-popper, a brawler? Come as you are.

Are you gay? Come as you are (but don’t stay as you are).

Our church regularly preached about same-sex attraction. The words gay, homosexual, queer, trans were rarely used. Our good bible-teaching, bible-preaching church’s position was that being attracted to a person of the same sex was not a sin, but acting upon it was. There were testimonies given from men and women who “struggled” with same-sex attraction, but had repressed acting on those feelings with the help and guidance of the Holy Spirit. And we, the good, exemplary Christians that we were, applauded and amen’d.

In the car ride home, Simon and I would say things like: “Yes, I agree. It’s not a sin to be attracted to anyone. But is it reasonable to ask people to never have sex? To never fulfill that desire?” We didn’t know. And we’d say things like: “Of course, I don’t have a problem with gay people. I have friends who are gay. But what about those scriptures? They’re pretty clear about it being an abomination. But it’s just the sex that’s the abomination, not the person.”

Our kid listened quietly to all those sermons, testimonies and conversations for years.

At home, we pondered aloud, “What if the foster agency places us with a girl who’s gay?” We pondered aloud, “What about our own kid? How would we keep them safe? These kids come from all kinds of trauma.”

And we said things like, “But of course, we’d welcome any child. Just like at church: Come as you are (but don’t stay as you are).”

Our kid heard it all.

Once, I bought a copy of Neil Gaiman’s The Sleeper and the Spindle for us to read together as a family. While reading it, it became apparent that there was no prince to break the sleeping spell with true love’s kiss. Instead, a girl would kiss the sleeping princess. We had a serious talk with our kid about why we felt the book didn’t have the right message for our family. "Should we donate the book?” I asked Simon aloud, “I mean, should any child be reading this?”

Our kid was thirteen at the time, struggling with body dysmorphia, self-harm and an eating disorder, and seeing a therapist every week—a good Christian therapist recommended by the good private Christian school where our kid was a student.

As our kid grew older, they shrank, and God became bigger in our house to take up the space our kid left behind. There was praise music and Christian parenting podcasts played, and Bible verses beautifully inscribed on mirrors and bedroom walls. There were stacks of Bibles in every shade of pink that had ever been published alongside an array of studies: You're God’s Girl: A Devotional for Tweens, This Is Now: A Girl-to-Girl Devotional for Teens, Pretty Little Truths: Modern Devotionals for Young Women, God’s Little Princess Bedtime Devotional. We never missed an episode of 19 Kids and Counting. We were fully invested in each Duggar kids’ courting story and eventual wedding.

And all our knowing was unknowing. And all our certainty masked any doubt or confusion. And all our blundering over the worth and value of our gay friends and my beloved niece, Tiffanie, felt valid. And when my sister made it clear that she would not accept her daughter’s identity because the Bible said it was an abomination, I said nothing.

When Tiffanie overdosed on heroin and the queer and gay-loving and affirming kids—her friends who loved her fully and completely—paid for her burial when we, her blood family, could not, I never thanked them because I was too afraid to go to the funeral. Too afraid of my family. Too ashamed at what we’d done. All I could do was take all that not seeing and not understanding and infuse it into all my prayers, seeking and begging God, “What happened? Was Tiffanie saved?”

What did we tell our kid? The truth: “Your older cousin died from a heroin overdose at 28 years old. She was gay, and the Bible says gay people don’t go to heaven. But I don’t think that’s true. I don’t want to serve a God like that.”

And our kid shrank, and shrank and shrank…

Was it something we’d done? Something we’d said? Was it the divorce? Was it their estranged father? Was it all the foster kids coming and going? Maybe we needed to spend more time praying. Maybe we needed to spend more time reading the Bible together as a family.

Good Christian friends suggested maybe it was all that anime. Maybe it was listening to all that My Chemical Romance and Pierce the Veil and Panic! At the Disco and Lana Del Rey and Melanie Martinez. Maybe it was too much screen time. Maybe it was a demon that needed to be cast out. Maybe you should go to your prayer closet. Do you have a prayer closet? Have you seen the movie War Room?

Yes and yes. Three times.

One night, our kid couldn’t sleep. The therapist said it was anxiety. She said anxiety was normal for teens like them who attended high-performing schools like theirs. They were sixteen. They were my one and only baby, still and always, my baby. I knew anxiety. I could pick it out from the nuance of concern or worry. They weren’t anxious. My baby was inconsolably terrified. Of what? The dark. The light. Their desk facing a window. Their closed closet door. Showers. Their shadow. A sudden breeze. The Party City store. The premonition of any hint of change, and everything was always changing.

That night, I made up the sofa for my baby and I to wait out the darkness, arranging our pillows to meet at the elbow of our oversized L-shaped sectional. We watched Finding Nemo. When the movie finished and there was no movement but the rise and fall our breathing, I slowly reached for my phone, opened my Bible app and started softly reading aloud:

In the beginning God (Elohim) created by forming from nothing the heavens and the earth. The earth was formless and void or a waste and emptiness, and darkness was upon the face of the deep primeval ocean that covered the unformed earth. The Spirit of God was moving, hovering, brooding, over the face of the waters. And God said, “Let there be light”; and there was light…

My baby’s head lifted, “Read that part again, Mommie.”

In his book The Genesis Meditations, Aramaic and Hebrew scholar Neil Douglas-Klotz offers a meditation for the King James Version of Genesis 1:2 “And the earth was without form and void.” May we receive it:

Our individual existence,

The sense of self and integrity

That we see in every being

is at this point still existing

as something living, yet latent.

We can only call it by names like:

a watery formlessness,

spreading destruction

like a mythic sea monster, and

an earthy emptiness,

devouring life and food,

like a mythic land monster.

Life as we know it

as this moment of creation

flows between

existence and nonexistence,

like the state we experience

just before sleep and just upon

awakening.

Yet this seeming chaos

holds great power and

possibility in its womb.

It is the germ of the seed of life,

awaiting its time to sprout,

or even the dream of the germ

waiting in the petal of a flower

as the winter wind

blows it away.

Telling our good Christian family members that our kid was gay and trans-non-binary and would no longer be called the name I’d given them at birth was the easy part. Simon and I witnessed the change from dark to light in our child. All those years of wondering—“Is it this? Is it that? Did we do something wrong?”—all that worry was gone and replaced with the regular worry of just parenting. It was like we’d been in a sealed room breathing the same old stale air day after day and just at the moment when there was no oxygen left, someone opened a window. We guzzled this fresh air.

Of course, there were new worries to add to our old ones about them existing as a Black child in an anti-Black world. Now we worried for their safety in an anti-Black, homophobic, transphobic world. We were battling the same demon, but now this demon had grown an extra row of teeth and an extra tail and an extra layer of scales on its skin. But our kid? Our kid—their joy, their fullness, their embodiment—was impenetrable to its claws.

Our good Christian family members said things like: “Of course we love her. But what if she changes her mind?” We said, “Not her but them; not she but they.”

Our loved ones said things like: “I love her but calling them ‘they’ goes against my personal beliefs,” and, “We’re too old to change,” and “What if she changes her mind? Then what?” and, “We love her, but it’s an abomination.”

These loving family members weren’t being monsters. They weren’t being heartless or cruel. They were being good, exemplary Christians who were inconsolably terrified of an inconsolable and terrifying God that they’d been told needed their fear.

Our kid made boundaries but loved them still: Come as you are (but don’t stay as you are). Perhaps someday these concerned loves ones will be less afraid.

Our extended family is afraid of what “they/them” means to their understanding of what it means to be a human. “But it’s plural,” they plead. “How can someone be plural?”

These are good, exemplary Christians who believe deeply in the Trinity. When I remind them of this, they have no answer.

In her book, Womanist Midrash: A Reintroduction to the Women of the Torah and the Throne, Hebrew Biblical scholar and professor, Wilda C. Gafney writes:

Though the Divine is articulated with feminine and masculine gender in the Scriptures, in translation and tradition God became virtually exclusively male. The gendering of God’s Spirit as feminine calls for the feminine pronoun, yet generations of sexist translations have gotten around this by religiously avoiding the pronoun altogether. So in each case the text will say, “The Spirit [verb]. . . .” No unacceptably feminine pronoun is needed. But she is still there.

My family is no different than many good Christians who’ve forgotten that if God is indeed three-in-one, and if male and female are reflections of God’s image, then the complete Being of God can’t be only He or only She, but only They.

And they forget that when patriarchal Bible translators translated Genesis 1:26, “Let us make man in our own image,” the key words are plural, “Us” and “Our.” And is not God one? Apparently, this conundrum made them uncomfortable, so they usurped the Hebrew word “a-dam,” which means “humankind”, with “man.”

But God can’t be altered by mistranslations when Their creation bears so much evidence. When Moses asks God, “What’s your name?” God’s answer is affirmatively, definitively non-binary: “I AM WHO I AM.”

Even the Aramaic word for Jesus’s reference to God as “Abba” is derived from the root word “abwoon” whose original roots don’t specify any gender. Douglas-Klotz translates the word as “divine parent or birther.” What else would Jesus call God but “Abba” if indeed he is part of the triune and the Spirit is the “ezer,” Eve, the mother?

We quoted scriptures to our family members: “You knit me together in my mother’s womb…” and “How often I wanted to gather your children together [around Me], as a hen gathers her chicks under her wings…” They inhaled in shock and thought us heretics.

We said, “But this is the same kid you’ve always loved. The same exemplarily good kid who loves everyone. Isn’t our kid’s joy and peace proof enough?”

They could not hear us.

Looking back on that night, I see that I was right – my baby was more than anxious. But I was also wrong. They weren’t inconsolably terrified. Our kid was a “seeming chaos of great power and possibility, a watery formlessness, spreading destruction, an earthy emptiness, like a mythic land monster, devouring life” as they knew it (as all teenagers do) in a moment of creation flowing between what existed before and what had yet had room and space and time to exist. Our baby was “just before sleep and just upon awakening.” It would be another three years before the blessing of light—self-consciousness, the dawn of knowing—reached them.

And when that light finally revealed its truest and brightest reflection, I could refuse its light and continue to brood and hover over the formless void it left behind, or I could reflect back to it the Image of God within me and join in the singing of their incantation of creation: “Let there be light.” After it became clear that our kid had a fuller existence away from the home we made for them, I chose the latter. I would sing, “Let there be light.” So I asked, “Can we pick a new name for you?”

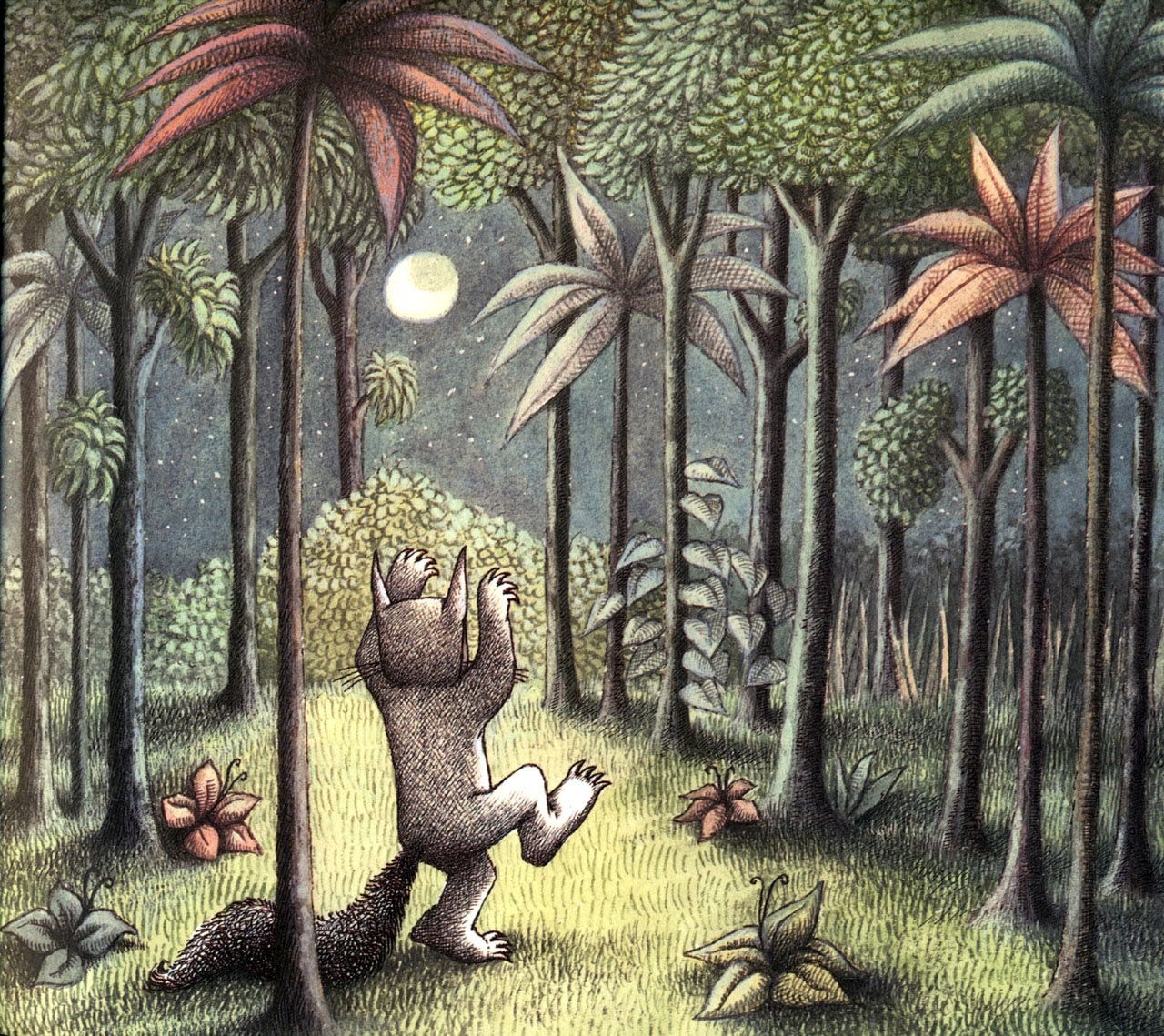

We chose Max, after Max from Where the Wild Things Are. And when we revealed the name to our kid, they became, well… Max. All wolf, all light, all love.

“Let there be light.” And then there was.

And in that light, Max wanted to be where someone loved them best of all. And so they traveled back over the years, and in and out of months and weeks and days, to find their whole self in their very own home where we, a triune force of Mom, Dad and Stepdad, were waiting for them.

As a mom with a non-binary child, I thank you for this from the bottom of my heart. I have overflowing good tears this morning.

This is sacred.

Sacred.

Sacred.

Oh, thank you. You didn’t have to give us this. It’s a rib from your side.

It costs.

It’s forming us.

Thank you.