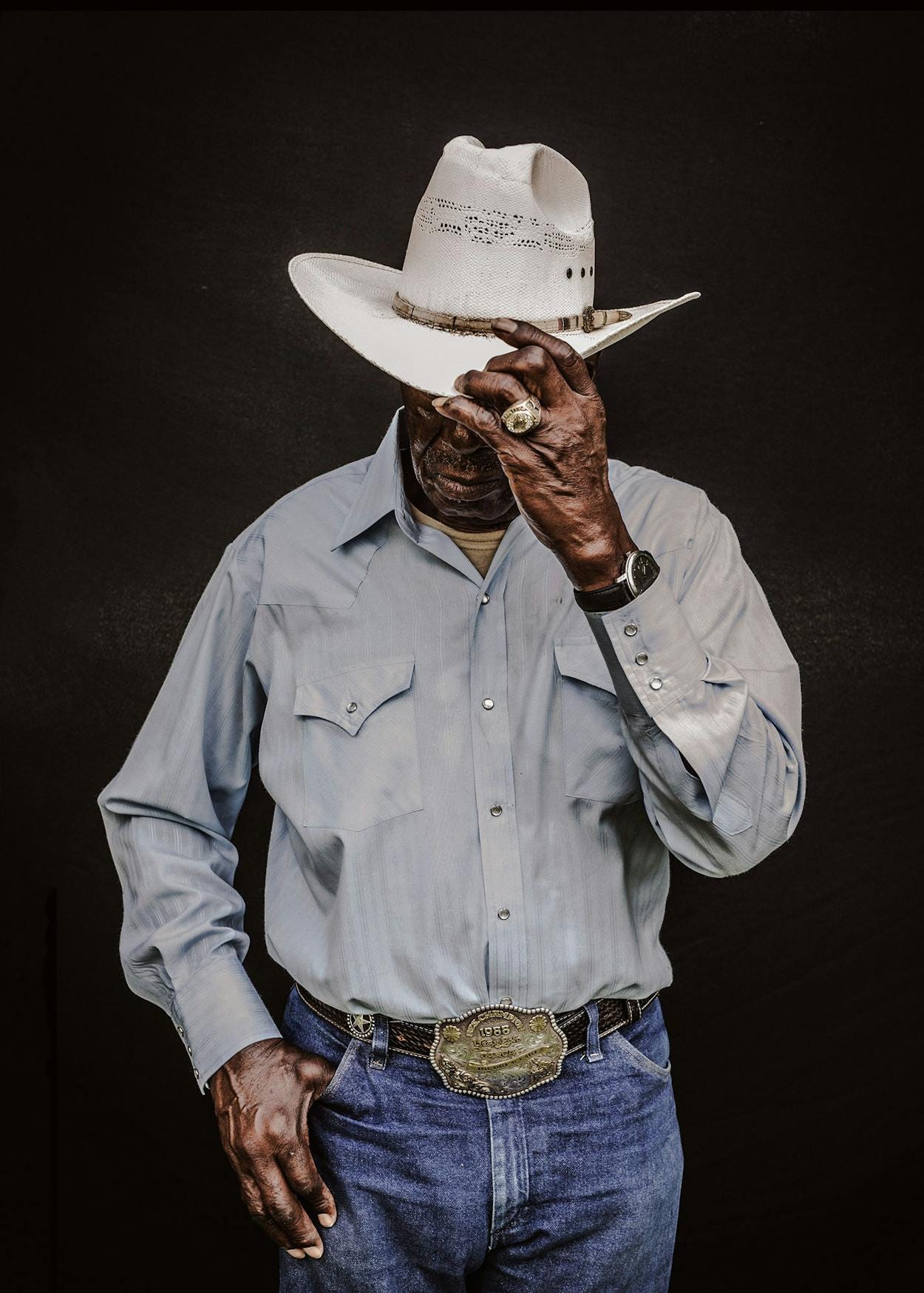

Myrtis Dightman (aka the Jackie Robinson of Rodeo) for Texas Monthly

But what I don’t understand is why America is surprised to discover Black people love country music? Most of us—56 percent—live a-way down South in the land of cotton. ’Course we like country. Our people were born in those fields (and picked them).

The ones that flew away took those seeds of Carolina rice and grits, denim and rhinestones, wide hats and even wider grins with hearty handshakes and Pullman’s neighborly back slaps followed by a “How ya doin’? I ain’t seen ya in a month of Sundays,” and planted them all up North.

No assimilation needed, we migrated Midwest and Northeast and settled down on southern haunches – sitting on porches in the evening and planting collard greens, okra and tomatoes in the backyard. We put down roots onward and upward and added a dash of Frank’s Red Hot Sauce to everything and did our Kool Aid as dirty as our sweet tea.

We kept our “Whew chile,” and “Lawd have mercy,” and “Well, ain’t that a blip.”

We toasted the blessings of marriages and babies and graduations, drinking sherbet punch out of mason jars.

Black people been country. We will always be country. We will always love the country like a pecan tree loves the wind.

Find an audio reading of this Black Eyed story above.

The day after Cowboy Carter was released, I received this text from my older sister, Mia, and my oldest cousin Denise:

Hey Sis if you haven’t already please listen to Beyoncé’s new album. It’s a masterpiece. She shut the haters all the way up. Damn… 🤣🤣🤣

I hadn’t listened yet but we continued texting, thrilled to feel included for once in a genre we so loved. For the first time we didn’t have to worry if it was for us. We didn’t have to worry about being seen or understood. We didn’t have to worry if the singer was Reba/Dolly/Willie-country or God-Bless-the-USA-country.

Two weeks later, I finally listened to Cowboy Carter. I listened to it three times in row. The first time I listened while walking through my diverse, Sesame Street of a neighborhood on my way to the Trader Joe’s bustling full of color from the flowers to its cashiers and shelf stackers. My eyes glistened to:

Sixteen carriages drivin' away

While I watch them ride with my fears away

To the summer sunset on a holy night

On a long back road, all the tears I fight.

Competitors watch the opening ceremonies at the 1977 Texas Prison rodeo in Hunstville. Texas Highways

Whenever I came home from college on summer break, my sister Mia and I were inseparable again like Peaches & Herb, Bert & Ernie, Shaggy & Scooby, Scout & Jem, Ashford & Simpson. We’d gone from sharing a room and a closet and watching the three seasons of A Different World together to watching Dwayne and Whitley’s wedding in the season five finale – 20 miles apart. We tried to restore our faith in one another whenever I rode shotgun with her on our way to the Pick n’ Pay or the mall or the gas station. Her red Ford Escort became our SXSW where we held panel discussions on TV, music and movies.

I wanted to know what she thought of House Party (she hadn’t seen it yet). She wanted to know if I’d listened to Johnny Gill’s new album (I had but wasn’t into him). She wanted to know what I thought of the latest Steven Seagal movie Hard to Kill (nothing – didn’t know there was one). I wanted to know if she’d bought Soul II Soul’s CD (who? – she said). Without a moderator to help us meet somewhere in the middle, the best we could do was co-exist, side by side but noticeably apart – Siskel and Ebert, McCartney and Lennon.

The summer of 1990, we rented Steel Magnolias from Blockbuster Video one Friday night. We missed it in the theaters and were shocked to see the hooker-with-a-heart-of-gold from Pretty Woman playing the role of Shelby. We loved every bit of Shelby Eatenton Latcherie from the moment she said, “My colors are blush and bashful, Mama,” and we loved the movie inside our Ohio bubble looking at its southern setting through blush and bashful colored glasses.

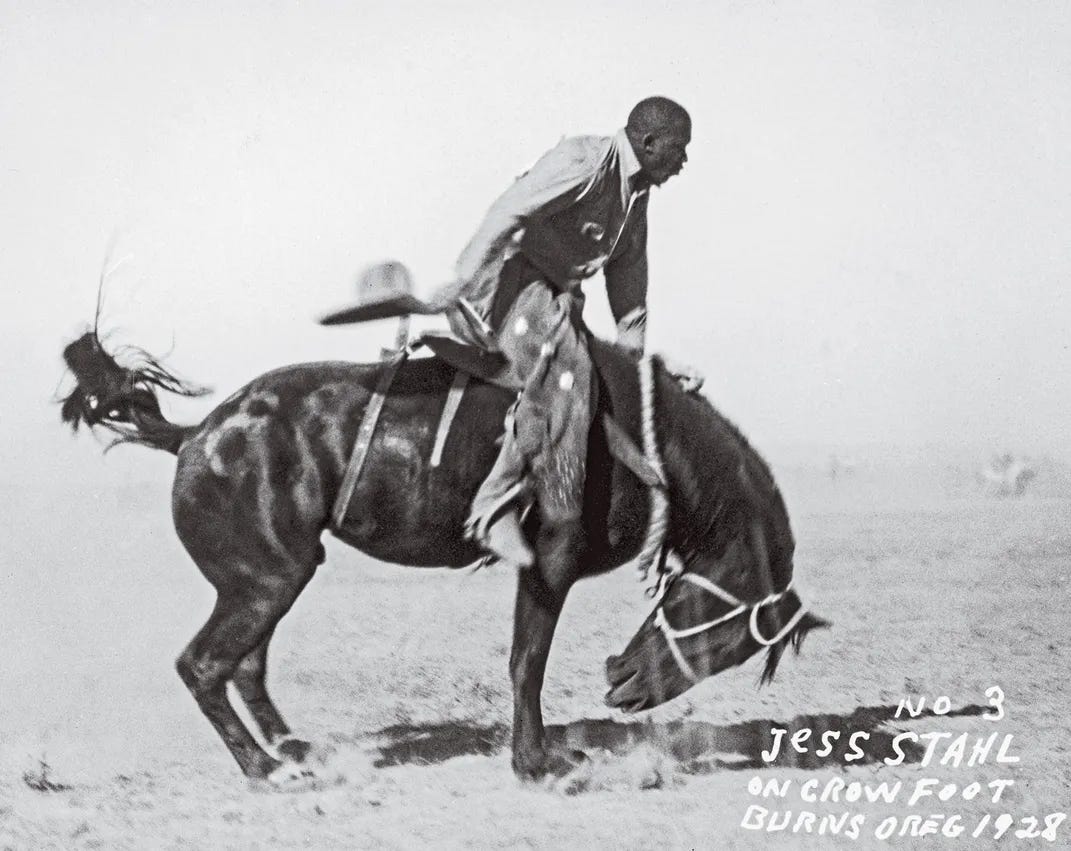

Jesse Stahl, considered one of the greatest bronc riders in history, in Burns, Oregon, 1928. Smithsonian Magazine

I dreamt of being Shelby minus the diabetes, understanding that American audiences could never suspend their disbelief long enough to watch a movie about a Black diabetic girl in Louisiana, declaring, “Pink is my signature color.” America had already decided that if a Black girl had diabetes it was her fault. “‘Course, she got diabetes. It’s all the grits with sugar, all the fried chicken, all the watermelon, all the sweet potatoes with marshmallows she probably ate that did it.” That she had type 1 wouldn’t matter to them. They’d just blame her mama, her grandma, her Black pastor, her Black school teacher, her very Black shadow. But I’d learned not to think on these things too long. As a grandbaby of Jim Crow, it was best to leave my blush and bashful goggles on whenever I cast my gaze upon the South.

And cast my gaze I did, to the South on TV: I’ll Fly Away, The Golden Girls, Evening Shade, Dallas, Reba, and my favorite, Designing Women; to the South on movie screens: The Man in the Moon, Something to Talk About, Eve’s Bayou, and Down in the Delta; to the South in books: The Prince of Tides, A Confederacy of the Dunces, and The Divine Secrets of the Ya Ya Sisterhood; to the South between the covers of magazines: Southern Living and Country Living (the latter wasn’t specifically southern, but it certainly had a slight southern twang and drawl).

Larry Mahan (aka the Elvis of Rodeo) competing in Oklahoma City in 1974. New York Times

When I finally met my British, red-headed hobbit from Austin, Texas, not a single friend asked if he was willing to move to Chicago. Everyone assumed I’d be the one to pack up and merge my life into his. I don’t know if it was because they all knew I took square dance lessons at the Old Town School of Folk Music in my neighborhood or if it was because I always played Neko Case’s Blacklisted, Ryan Adam’s Heartbreaker, and Old Crow Medicine Show’s eponymous album on repeat if given the opportunity to play DJ. Or maybe it was the rose-engraved cowboy boots I sometimes wore with my black denim floral-embroidered skirt. Maybe it was because the guy I’d dated before I met the hobbit was a rangy, honky-tonk fiddler.

Of course, they were right. I moved. After one particularly smug and inhumane winter with the shrillest of winds, becoming a Texan was a no-brainer. In 2010 I said “I do” in Chicago and after honeymooning in Wisconsin for three days, moved to Austin.

Fifty-six-year-old Willie Craig was the rodeo top hand of the Texas Prison Rodeo in 1976. Texas Highways

Though Roberts County, Texas is only 8 hours north of Austin, it might as well be on a different planet:

Nearly a million people live in Austin – just over 800 people call Roberts County home

There are just over 800 bars in Austin – Roberts County is an entirely dry town

7.9 percent of folks who live in Austin are Black – 2 Black people make up the 0.24 percent of Black folks who live in Roberts County

CNN went to Roberts County to do a piece they titled: 96% of This County Voted for Trump in 2020. Hear What They Think About the Hush Money Trial. As I watched the report, I couldn’t help but notice how beautiful Roberts County was. Yes, it was true its downtown Main Street was all but shuttered and abandoned, but it was encircled with rolling hills, golden fields, and live oaks. It was the town that America had forgotten. So of course, 96% of them love Trump. He made a promise to them to make Roberts County, Texas great again.