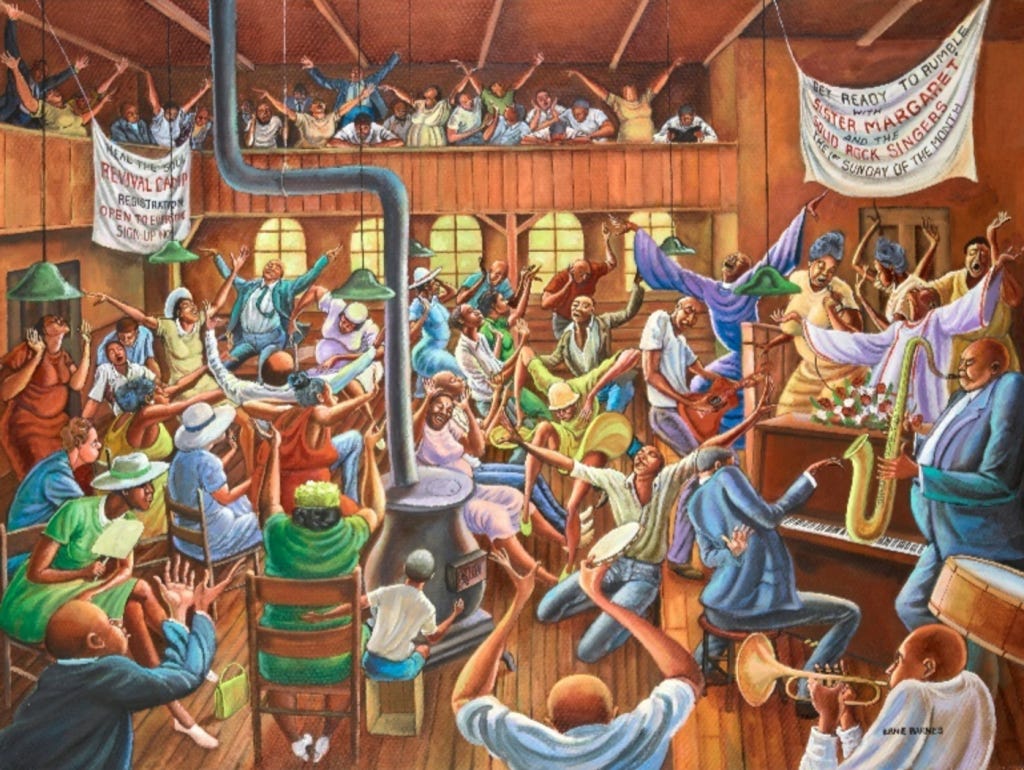

Artwork Pieces by: Ernest Barnes (July 15, 1938 – April 27, 2009), Durham, North Carolina

Before we begin, here’s a question on which I would like for you to reflect:

What comes to mind when you hear the phrase “Bible Belt”?

The most troubling thing, particularly for me as a Black woman, is that the largest protestant group in the country is the one with the most racist history – Southern Baptists, ie., the Southern Baptist Convention.

It so deeply disturbs me that the Bible Belt, so snugly wrapped around the South with the Ku Klux Klan, the White Citizen’s Council, and the Lost Cause muffin-topping hanging over its waistband, is finished with a shiny brass buckle embossed with the Confederate flag.

While driving through the winding hills of North Carolina with its glorious Blue Ridge Mountains standing like a verdant Hallelujah chorus, I vehemently resented the Church and its nerve to make itself so at home, so nestled within this lush landscape.

There are so many Baptist churches—more than convenience stores or gas stations. I sat rigid, pissed and pondering, looking out the passenger window in awe at this magnificent hedge of protection and its sweeping vista of racial prudence. I hadn’t seen a Black person since Indiana. Actually, I saw one at the Buc-ee’s in Kentucky, a cashier. And oh! How I wanted to save him.

We drove on. As we wended our way through Buncombe County, I felt unsure whether my heart palpitations and prickling skin were due to the overstimulation of my surroundings or my fear of not knowing what exactly surrounded me.

What history took place in the thick of all those trees?

How many Black bodies knew them intimately?

Since the age of eight years old, I’ve believed in the saviorhood and divinity of Jesus. Now at fifty-three, entering North Carolina, I questioned that deity and all those miracles, down to the virgin birth. I was taught to believe with my whole heart, “yes, Jesus loves me, for the Bible tells me so.” Yet we passed all those churches—all those Brides of Christ—and I felt anything but saved by them. I felt anything but safe with them. I didn’t want to join any of their heavenly hosts. They clearly weren’t inviting me to join the wedding celebration. It was so obvious. Every white church sign with black letters told me “you’re not supposed to be here.” They did so graciously. It was subtle. The“Jesus saves” billboards or the “John 3:16” painted on the side of a barn told lies like the serpent in the tree. Only these trees didn’t offer me forbidden fruit but a noose on which to hang my Blackness.

My belief in Jesus and my commitment to love would not have saved me in North Carolina. Before crossing into its borders, I couldn’t remember the last time I was called a “n*gger” within meaningful, intended-for-me-to-hear earshot. And though I’d braced myself to receive a few passing looks of white repulsion at my daring to live well in my dark skin beside my white husband, I hadn’t prepared myself for the slur. I was so focused on all the Blue Lives Matter flags waving from front porches, and Biden Is Not My President, and Let’s Go Brandon yard signage, I’d forgotten the word was still used. I was so deaf to it that I wasn’t even the one who heard it first. Unfortunately, it was my 20-year old Black queer child and my friend’s 13-year-old white daughter who alerted me, in unison, that yes I had heard what I thought I’d heard as we made our way along the main shopping boulevard in downtown Asheville.

I’m an old broad, so the word didn’t even break my skin. But the look on those two faces—those Gen Z faces—blew a hole through me. Their immediate want for an explanation made the wound sick with gangrene: “He’s just a crazy homeless man…” “He probably didn’t even know what he was saying…” “I think he had Tourettes’….”

I don’t want another generation to have to make excuses for the previous generation’s ignorance. I wanted to tell them that a disabled, homeless man in a wheelchair who has the time to mutter such a curse shouldn’t have the time or energy to cast any kind of opinion on my skin. I wanted to tell them that his “fuckin’ n*gger” only means he held this hatred long before he lost his leg, long before he lost his home, long before he lost his mind, long before his before. His epithet only proved that, like so many other white people, he blamed my wellness for his every misery. I knew he’d only said what those who were white, able-bodied and doing just as well as me or better certainly felt. He said it out loud; they said it with quick glances and smiles and extra, special, “grace-required” southern politeness. But I allowed their young hearts to erase rather than to process all of this. After all, we were on our way to get their second ice cream of the day, because we were on vacation.