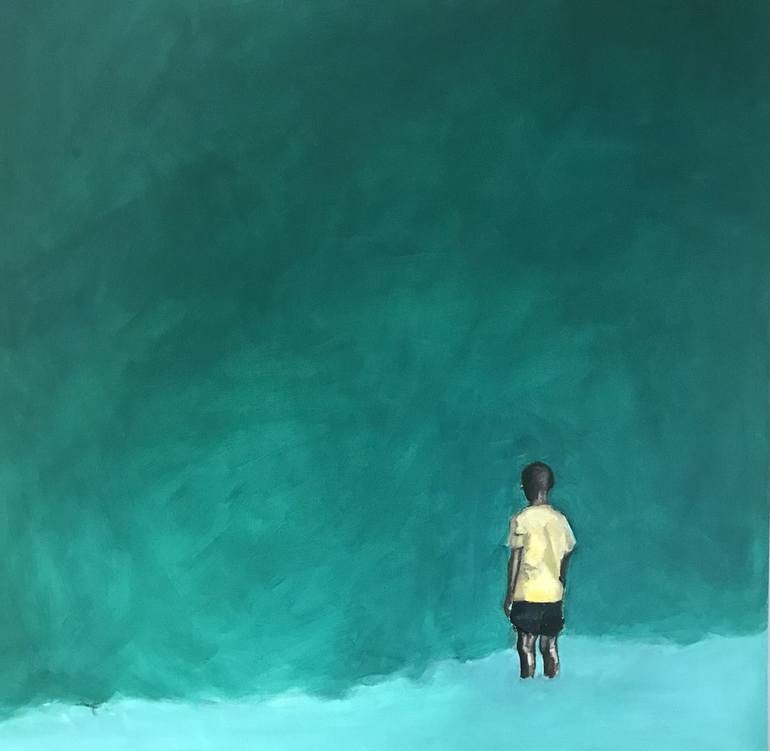

dimeji onafuwa | The Unknown Unknown

When my mother was charged with involuntary manslaughter and sentenced to serve 8 to 25 years in Ohio’s state penitentiary for women, everybody on her block and family tree said, “Poor Nada, she’ll never make it. Lawd have mercy.”

Sure she had killed, but only when backed into a corner and about to be killed herself. And though in her past she’d been violent, in her twilight years she’d been practically a pacifist. All peace and love—no drama. And since she was past her prime (damn near sixty) she was not up for the job of prison stud or commissary hustler. If she’d gotten locked up in her younger years, none of us would have doubted her ability to rise amongst the prison ranks and maybe even charm the guards and the warden. But at damn-near-sixty, we all lamented, “Poor Nada… she’ll never make it. Lawd have mercy.”

But lo and behold! Not only was my mother cut out for prison, but her extended stay was bashert—meant to be and perhaps even pre-destined by G-d. It suited her so much that she thrived, getting her GED and even her Associate’s Degree. And if those academic achievements didn’t prove us wrong, then her engagement did. Tell me: what woman at damn-near-sixty goes into prison single and comes out with a ring on her finger? My mother. Nada P. Jones. That’s who.

During her first inmate call from prison, the first thing out of her mouth was, “Y’all, it looks just like a college campus. You wouldn’t know it was a prison except for the barbed wire.” And we all sighed, relieved. Yes, our mother was in prison. But we were grown and grateful that she hadn’t succumb to this fate while we were children. We were grown now—still traumatized, but at least able to cook for ourselves and tuck our own bodies into bed.

But wait— this is what I want to tell you: my mother went to prison and all we could do was love what we knew to be true – the past events that led to this event. Thus we all moaned, “Poor Nada… Poor Nada… Oh Sweet Jesus, Poor Nada… Oh Lawd, Have Mercy!” We only knew despair and bad news and hard times. We only knew how to love what we knew. To accept the familiar waves of tragedy and trauma and love it all anyway.

We had yet to learn to how to love the unknown. For us, there was no such thing as hoping for the best, looking at the glass half full. Our eyes were so heavy-lidded. What was the point of rose-colored glasses? We loved what we knew.

How could we have loved the unknowns of Nada in prison? We didn’t know how to embrace the mystery of expectation. We’d grown up learning how not to expect too much, or try too hard, or to dream at all. We were Nada’s children. For damn-near all of our lives we watched my mother lose and lose, again and again. The only thing unknown was which tragedy would be the next one to befall us all – which crime against humanity would be the next to arrive at our front door. The unknown was never mysterious, but instead forever dreaded.

Let’s skip ahead, decades later: I am grown. Nada is long laid at rest. There is still no peace.

When our kid Max was institutionalized without our knowledge or blessing, the legacy of Nada’s trials and tribulations unfurled. When the psychiatrist told us, “it’s bipolar,” I despaired, just like I did when I heard “involuntary manslaughter” and “8 to 25 years.”

May this unknown not be fated. May we embrace the mystery of expectation. May we expect more than we ever dared. May we try hard. May we dream even the tiniest of dreams.

In the Genesis story, the unknown is “formless and void or a waste and emptiness, and darkness was upon the face of the deep,” and God loves the unknown into stars, sky, earth, and water. God loves it into grass, flowers, trees, and crawling and slithering and flying beasts. God loved the formless void of unknown nothingness into knowable reflections of God herself.

I do not know what will happen with this formless void and waste and emptiness and darkness that is deep and swirling called bipolar disorder. I only know the smallness that I have known, which is too myopic to imagine what can be created from despair. So I pray for Max, “Let there be light,” and I imagine my mother on high fashioning my prayers into amens.

Thank you for this Pentecost reflection about faith in the face of the unknown, and courage to imagine grace of transformation without knowing what and how. How real your prayer: “May we try hard. May we dream the tiniest of dreams.” Peace and blessing to you and yours.

Stunning.