Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe aka A Little Old Lady's Charming and Sweet and Racist Memoir

A Black Eyed Review of Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe by Fannie Flagg & MAGA

Harper Lee, the reclusive author of the unfortunately too-much-beloved novel To Kill a Mockingbird, loved Fannie Flagg’s book, Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe:

"Airplanes and television have removed the Threadgoodes from the Southern scene. Happily for us, Fannie Flagg has preserved a whole community of them in a richly comic, poignant narrative that records the exuberance of their lives, the sadness of their departure. Idgie Threadgoode is a true original: Huckleberry Finn would have tried to marry her!”

Harper Lee, Reader’s Digest

Lee, like many others, loved the book because of the nostalgia it provoked in readers of a time when White people were good and kind owners and masters of propriety and culture – and Black people were just happy not to be enslaved.

Flagg’s Fried Green Tomatoes, published in 1987, has left an indelible mark on our country’s collective racial consciousness, just as Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird did in 1960. Each taught readers—and later, movie audiences—that racism is a matter of the heart – individual, not systemic.

Find an audio reading of this Black Eye Book Review above.

In 2021, The New York Times asked its readers, “what’s the best book of the past 125 years?” The answer from 200,000 ballots that came from all 50 states and 67 different countries was To Kill a Mockingbird. The book narrowly beat out JRR Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: The Fellowship of the Ring, with George Orwell’s 1984, Gabriel García Marquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude and Toni Morrison’s Beloved as the runners-up.

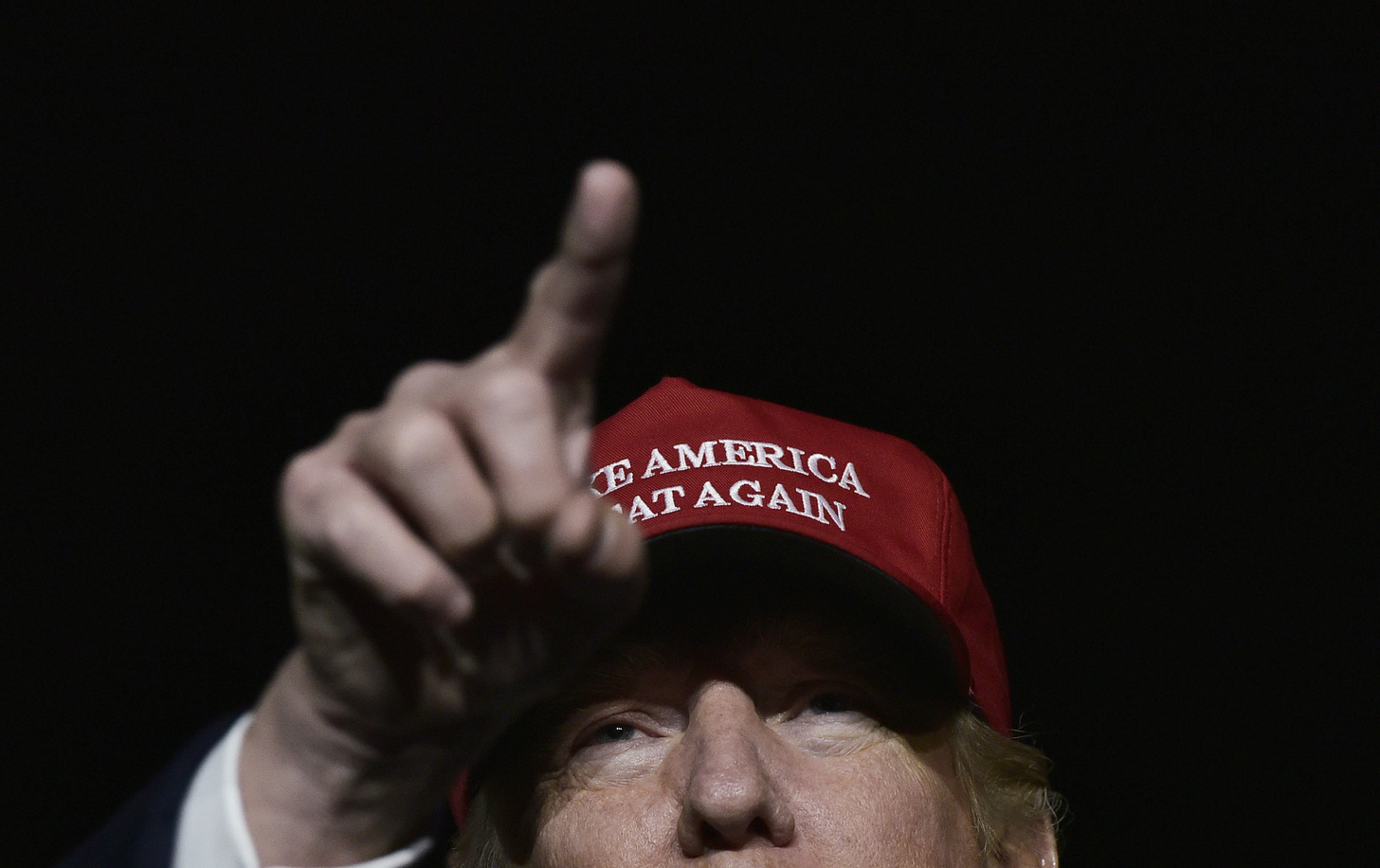

Let me put this into perspective: after four years of a Make-America-Great-Again Trump presidency, and after the lynching of George Floyd, and after Black Lives Matter protests across the world, and after the Instagram black squares, and after bestseller’s lists flipped from all-White authors to all-Black authors, and after books like Ibram X Kendi’s Stamped from the Beginning and Austin Channing Brown’s I’m Still Here sold out in bookstores, and after the 1619 Project broke print news records… readers of The New York Times—who are progressive, liberal, and college-educated readers—said To Kill a Mockingbird was the best book of the past 125 years.

Y’all, America has a problem: its addiction to nostalgia is killing us.

Though I’d already read the book and seen the movie in my 20s, I recently listened to the audiobook of Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe. I was looking for something, I don’t know, charming? Delightful? Comforting? When the book popped up on a couple of lists, I thought it’d be perfect. But in 2024, I’m not as easily comforted. Back in my 20s, I loved the story without questioning its message because it was funny and sweet and, well (dammit, I’m just gonna admit it) a colorblind, I-don’t-see-color mentality had it rewards in 1991.

In the 90s, we all accepted the stories that White authors and filmmakers told us about what it was to be Black in America. Audiences bought armloads of books and packed movie theaters while wearing colorblind googles as if watching racism in 3D. As long as a movie or a book was set in the old-timey, backwoods, racially-inbred South as opposed to the progressive, integrated and post-racial North, it was sure to be a hit. As long as it made a clear distinction between good White people and bad White people—and the good White people were good White Saviors—the story was widely praised and accepted.

In the 90s, White-authored books like Melinda Haynes Mother of Pearl and later in the early 2000s, Kathryn Stockett’s The Help were bookclub favorites, and White-directed movies like Driving Miss Daisy, Glory and Mississippi Burning were all blockbusters. Even Steel Magnolias and The Prince of Tides were considered bonafide and historically accurate in regards to their lessons about the good old South, even though they avoided treading on any of the South’s racial strongholds by simply not featuring Black characters.

Revisiting Fried Green Tomatoes was a self-inflicted hate crime. I’m not even joking. The use of the n-word comes up 32 times and most always by a White person—you know, the bad kind of White person, while the good White people—the actual heroes of the story—speak of Blackness either as a mysterious affliction or an entertaining and enviable personality trait:

“Isn’t it odd, the colored want straight hair and we’re always wanting curly hair?”

“… you never know where colored people come from.”

“Course, you can never really tell how old colored people are.”

“After she left, Mrs. Threadgoode made the observation of how peculiar it seemed to her that colored people came in so many different shades.”

“She said it nearly broke her momma’s heart when she married George, because he was so black. But she couldn’t help it, said she loved a big black man and George was sure the biggest and blackest man you ever saw.”

“Artis was so black he had blue gums. Onzell said she couldn’t believe that something that black had come out of her… and you cain’t get any blacker than that!”

“And then came Naughty Bird, as black as her daddy, with that funny nappy hair…”

“Idgie says that Sipsey, her colored woman, grew a stalk of okra six feet…”

“I know for a fact some of those colored women ate clay right out of the ground.”

“Vesta Adcock ran over her colored yard man, Jesse Thiggins, on her way to her Eastern Star meeting on Tuesday.”

“And the colored people on the TV now are not near as sweet as they used to be… I never saw such behavior. There’s no call to be that ugly.”

“I’ve been around colored people all my life… Why, when Momma Threadgoode died… one by one, every colored woman from Troutville had gathered out in the side yard, there by the window, and they started singing one of their old Negra spirituals, ‘When I Get to Heaven, I’m Gonna Sit Down and Rest Awhile’. You’ve never heard singing like that, it still gives me goose bumps just to think about it.”

“You know, a lot of these people resent having colored nurses out here. One of them said that deep down, all colored people hate white people and if those nurses got a chance, they’d kill us off in our sleep.”

“So there’s not a person alive that can tell me that colored people hate white people. No sir! I’ve seen too many sweet ones in my life to believe that.”

“They can do most everything better. I wish I was black.

You mean colored?

Yes.”“Well, they’re all right, but I don’t care what you say, colored people can make barbecue better than anybody in the whole world.”

“Just thank the good Lord He made you white. I just cain’t imagine why anybody would want to be colored when they don’t hafta be.”

But if you want to understand what colorblindness looked like in the late 80s in the hands of a White author born and bred in the south, here’s a passage that sums it up:

All her life she had considered herself to be a liberal. She had never used the word nigger. But her contact with blacks had been the same as for the majority of middle-class whites before the sixties—mostly just getting to know the maids or the maids of friends.

When she was little, she would sometimes go with her father when he would drive their maid to the south side, where she lived. It was just ten minutes away, but seemed to her like going to another country: the music, the clothes, the houses… everything was different.

On Easter they would drive over to the south side to see the brand-new Easter outfits: pinks and purples and yellows, with plumed hats to match. Of course, it was the black women who worked inside the homes. Whenever a black man was anywhere nearby, her mother would get hysterical and scream at her to run put on a robe because, “there’s a colored man in the neighborhood!” To this day, Evelyn was not comfortable with black men around.

Other than that, her parents’ attitude about blacks had been like most back then; they thought most were amusing and wonderful, childlike people, to be taken care of. Everyone had a funny story to tell about what this maid said or did, or would shake their heads with amusement about how many children they kept having. Most would give them all their old clothes and leftovers to take home, and help them if they got in trouble. But as Evelyn got a little older, she didn’t go to the south side anymore and thought little about them; she had been too busy with her own life.

So, in the sixties, when the troubles began, she, along with the majority of whites in Birmingham, had been shocked. And everyone agreed that it was not “our colored people” causing all the trouble, it was outside agitators who had been sent down from the North.

It was generally agreed too that “our colored people are happy the way they are.” Years later, Evelyn wondered where her mind had been and why she hadn’t realized what had been going on just across town.

After Birmingham suffered so badly in the press and on TV, people were confused and upset. Not one of the thousands of kindnesses that had taken place between the races was ever mentioned.

But twenty-five years later Birmingham had a black mayor, and in 1975, Birmingham, once known as the City of Hate and Fear, had been named the All-American City by Look magazine. They said that a lot of bridges had been mended, and blacks, who had once gone north, were coming back home. They had all come a long way.

When Nikki Haley said, “America has always had racism, but America has never been a racist country,” or when the former president said, “You had many people in that group other than neo-Nazis and white nationalists. The press has treated them absolutely unfairly. You also had some very fine people on both sides,” we have to look back at all the whitewashed, colorblind books and movies we continue to endorse and praise that helped to create their deeply held beliefs. They believe that racism is only swastikas, burning crosses, white robes and hoods, the n-word, “Whites only” signs and blackface, but not the Confederate flag, which Haley claimed stood for "service and sacrifice and heritage,” before being forced to remove it from South Carolina’s Statehouse grounds after losing a 4-year battle thanks to photos that mass shooter, Dylann Roof, posted of himself posing with that symbol of "service and sacrifice and heritage" before gunning down Black worshippers at a historic Black church during her governorship.

Earlier this month while giving a speech to the Black Conservative Federation, Trump said, “These lights are so bright… my eyes… I can’t see too many people out there. I can only see the black ones. I can’t see the white ones,” and received chuckles from a mostly Black audience. His supporters didn’t feel this comment was racist. But I wonder if they’d have felt the same way about his little joke if he’d said it while wearing a white hood and robe while carrying a flaming torch in one hand and a Confederate flag in the other. Or maybe, he would have had to say: “These lights are so bright… my eyes… I can’t see too many people out there. I can only see the niggers. I can’t see the white ones,” in order to rouse them from their colorblind delirium that accepts his claim that his mugshot and his gold sneakers make him more relatable to Black voters.

Americans are conditioned to see sweet old lady characters from movies like Fried Green Tomatoes and Driving Miss Daisy as just innocent and, well, southern. They don’t equate them with the racism of a Klan member or a Proud Boy insurrectionist. They aren’t as quick to call out their ignorance as they are to call out Mike Pence’s or Ron DeSantis’s when they say that systemic racism doesn’t exist and wokeism is anti-American.

Today, right now, the book Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Cafe has 4.28 stars out of 5 on Goodreads with 305,628 ratings and 9,855 written reviews. Out of the 305,628 ratings, 2,067 are 1-star reviews.

Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which came out the same year, has more ratings (432,397) and more reviews (21,128) with only 3.95 stars. Out of the 432,397 ratings, 15,664 are 1-star reviews.

Fried Green Tomatoes didn’t receive any literary awards, but Fannie Flagg did receive the Harper Lee Award for Alabama’s Distinguished Writer of the Year in 2012 and her book spent 36 weeks on the NYTimes Best Seller List.

That same year, Beloved spent 10 weeks on the NYTimes Best Seller List. Like To Kill a Mockingbird, it also won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction. And though it was nominated for a National Book Award, it didn’t win, even though several prominent authors protested the snub. It did win the Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Book Award, the Melcher Book Award, the Lyndhurst Foundation Award, and the Elmer Holmes Bobst Award.

I would love to say that none of this matters and Hip-Hip-Hooray!!! for all authors who are “nice and kind and important.” But it does matter, because books tell the stories of our culture and what’s humane and what’s abhorrent, what’s socially-acceptable and what’s inappropriate, what’s worth protecting and what’s disposable.

I’m worried about the upcoming presidential election because in 2020, To Kill a Mockingbird was number 5 on the list of the most checked out books of all time from the New York Library. Y’all, the book came out in 1960, and in 2020 it was still beloved no matter all the anti-racist commitments that have been made. It doesn’t matter that we now know and fully understand the book’s problematic White savior narrative. And it doesn’t matter that there are now, and always have been, better books and better stories written by Black authors about racism in our country.

I’m worried because I know that if I just mention the movie or book Fried Green Tomatoes it evokes the same nostalgia as To Kill a Mockingbird.

I’m worried because readers continue to love these outdated books that have nothing to say about the interior lives of Black people, yet everything to say about how good and kind White people loved their “colored” help.

I’m worried y’all because candidates continue to say outlandishly racist and anti-Black things and nothing—not even our supposed racial reckoning—has stopped them.

I’m worried because we love these books and these movies where Whiteness is supremely good and Blackness is dependent on that goodness and there’s a man who’s vying to be a dictator, not a president.

And millions and millions of colorblind, White christians love him and thousands are willing do anything—including commit crimes—to make his dictatorship dreams come true.

This one was a reckoning for me... I haven't read Fried Green Tomatoes in a long time, but I do remember loving the book and the movie at the time... and now I have read all the quotes you pulled from the book and realize I didn't really read it, not really, not with an ear open to the actual words, not with a heart open to the full humanity of all the characters in the story, not with my eyes open to the constructs of racism that surrounds us always, in every single aspect of our lives here. Today I know better, so tomorrow I can, and will, do better. So much learning- and unlearning- to do! Thanks for shining a light in this space.

I *somehow* avoided the pitfalls of many of the most popular white savior narratives presented during my youth, but growing up in the south, they were still the prevailing narrative to understanding race. I have always been suspicious of things I am "supposed" to like, and it's probably the only reason I didn't fall all over myself to love these things, not because I was aware enough to know better. I do think it helped me be more open to the facts of the matter once I got to college and actually took an African American literature class where I was faced with the realization that being nice did not equal not being racist. I never once questioned the realization once it was presented to me, even though it was terribly uncomfortable. Thank you for sharing your always astute observations and giving a lot of us a chance to sit with uncomfortable realizations. I wish more people saw the value in these types of moments rather than immediately seeking the comfortable novocaine of lies we have learned to expect.