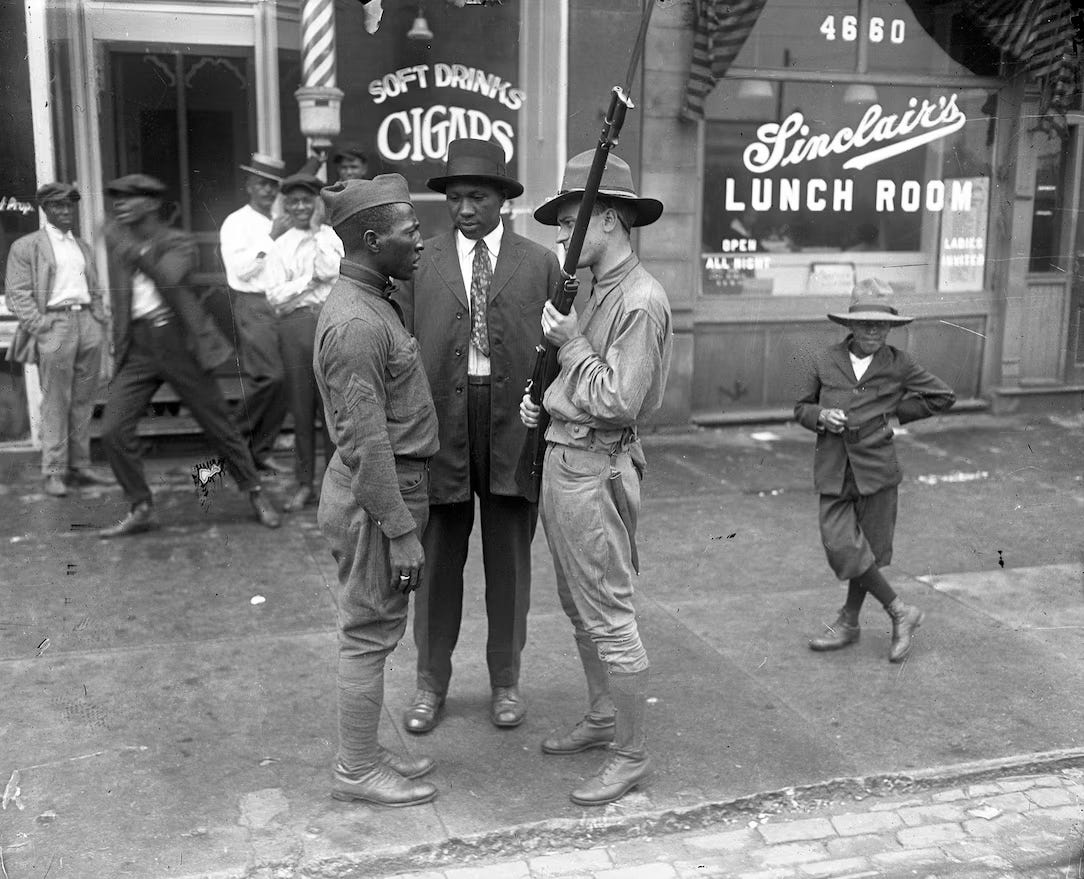

Chicago's South Side. 1919 Race Riots

Find an audio reading of this Black Eyed Story above.

In the mid 90s, the cultural phenomena of “random acts of kindness” took to the streets. People went out of their way to pick of the bill for the person behind them in Starbucks. Surprise moments of kindness were there for the taking. They fell as randomly and plentifully as acorns from a tree.

During this monsoon season of benevolence, my sister and I decided to take up running at a forest preserve. Day one, not even fifteen minutes into a light warm-up, a red pickup truck slowed to a crawl beside us. We thought, “Oh yay!” We were certain we were about to receive a “random act of kindness” but instead beer bottles and cans sailed from the windows and the truck bed followed by a stream of misogynistic racial slurs, howls and cackles.

This past Tuesday, my husband took the dog out for her late afternoon walk.

Same routine. Just after work is done, he shuts down his computer, pushes in his work stool, picks up his phone, scoops up the dog and heads for the door.

Same route. A couple blocks west and then a couple blocks north.

And home again home again, jiggety-jog, jiggery-jig.

At least that would’ve been the normal routine, but on this random Tuesday, from out of nowhere, a teenaged boy with a closed and angry first, cracked my poor husband upside his head, landing a weighted blow against his right ear.

“He fell before running away. But the two other kids, I think… I’m not sure… I think they asked if I was okay before running too,” he told me through pained, panicked breathing over the phone.

After my initial “What the fuck!?!?” I asked, “were they Black?” Then I held my breath, knowing the answer. I met him outside. Confused and defeated we finished walking Evie and headed back home slightly apart but mostly together.

My six-foot viking of a husband, drained of his usual boyish openness, couldn’t bring himself to speak aloud the unbearably difficult questions that will rise under such traumatic circumstances. Things like, “What did I do? Why did this happen to me?”

Sensing this but refusing to table my own fear-fledged frustrations, I scolded him, “You know you can always cross the street if someone doesn’t look right?” But I knew that my freckled gingerbread boy would never cross the street to avoid a stranger. Not only would he not want to be perceived as being racist, but also, the man knows no strangers.

I continued my concerned nagging, “I cross the street whenever I see a group of teenagers. It’s not about them being Black it’s about them being teenagers.”

I know. I’m telling my husband that I cross the street when I see a group of Trayvons and Michaels. I’m encouraging my husband to be wary of my own kind and I’m hating myself for it.

If I saw Ralph Yarl walking down the street, would I cross to the other side? What in the actual anti-racist-racist-nonsense was I talking about?

My husband for sure was not listening to me. “I don’t want to do that. I’m not gonna do that,” he said. “I don’t wanna live that way.”

And I threw my hands up, called my sister who I knew would side with me.

My husband believes even house centipedes are worth saving. Whenever one seeps through the cracks of our ancient abode, he carefully traps it beneath a cup and gently carries it outside – all the while worrying that he might hurt one of their eight billion legs.

My bearded, giant, furry-footed Hobbit of a husband is so tender to the feelings of others that he can sense when a hug is happening in another room, and will stop whatever he’s doing to run into that embrace, throwing his arms around it as if to say, “all hugs are ours.”

This is the man that gets punched in the head?

I was furious and sad to see him stripped of his nugget of belief that the world was largely good. But in a random moment, some man-child aimed and fired a sucker punch that struck at the core of his humanity.

Seems no matter where we live, my husband and I have drawn ire from gawkers who pass us by, whispering while launching pointed glances. Once when we were walking in our fancy gated neighborhood in Austin, Texas, a car slowed as it approached us, the passenger window lowered and a lit cigarette flew directly at us.

I’m still waiting to receive or even witness a random act of kindness, but I have a treasure trove of random acts of violence.

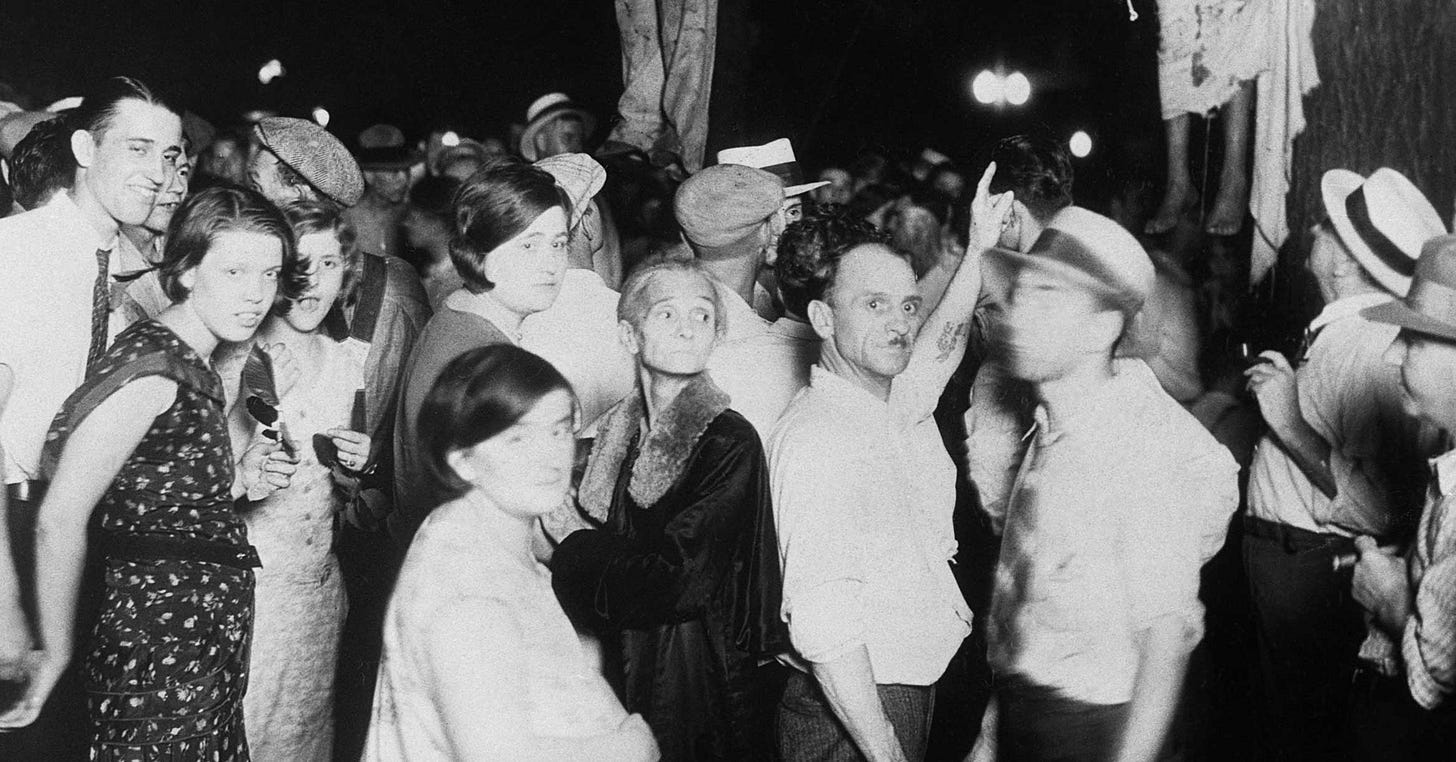

The Lynchings of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith. Marion, Indiana 1930

The trees can tell us stories of all the lynchings they’ve endured whenever Blackness was accused of touching or even just looking at Whiteness.

During our first phone call, before we were even officially dating, Simon and I had that conversation about what it would look like if we fell in love and got married. We talked about the looks we’d get. We talked about the comments. And he confessed to me a deeply held fear that people—White manly-men, to be specific—were always glaring at him, itching to fight him.

He’d told me about how once, in a men’s restroom at a bar, he’d overheard a couple of White guys having a conversation about whether or not they should beat up an eccentrically dressed customer for no other reason than they didn’t like that he was wearing a funny hat and a kilt. Though my husband didn’t wear hats or kilts, he felt his height, his red hair, his beard, his awkward shyness would only further enrage them. So he waited for them to leave before making his exit.

“Dating me will only make things like that worse,” I joked, knowing full well that together we’d never see the inside of a bar like that.

“Worth it,” he assured me.

I’d like to think it has been. But flaming cigarettes aside, there have been plenty of looks, plenty of snide comments, plenty of stares, plenty of snickers, plenty of moments that sent shivers of terror dancing up our spines. To be sure, whenever we travel by car, no matter the miles or the distance, we’re careful where we stop and we never stop to rest until we reach our destination.